Day of the Dead in Pomuch

Frida Kahlo used to say that she was more afraid of a life not lived than of death. In Mexico, her country, the cult of death is lived in a unique and ancestral way, similar to how the ancient inhabitants of the country lived it more than 3,000 years ago, when death represented the end of a cycle and the beginning of another. Back then, the goddess Mictecacihualt, known as "The Lady of Death" and wife to the god Mictlantecutli, "Lord of the Land of the Dead", was worshiped.

According to this "Day of the Dead" tradition, celebrated every year on November 1st and 2nd, the link between the living and the dead is maintained beyond physical death. It is believed that the deceased return every year to be with their family. For this reason, on these dates, different offerings and "altars" are prepared in houses and towns so that the dead don't forget to come back and visit in the future, in order not to break the family chain.

The Catholic evangelization of Mexico during colonial times changed the symbolism of many of these rites. On the other hand, current consumerism and globalization have distorted the true meaning of this tradition, reducing it to a series of tourist and folkloric celebrations in most places, but not in the entire country.

The "Catrina" skull is the symbol of the "Day of the Dead" in Mexico. The Great Lady of Death appeared for the first time in 1912.

Her creator was the Mexican illustrator José Guadalupe Posada. Its original name was "La Calavera Garbancera," and it was created as a criticism of the classism of Mexican society of the time.

In the province of Campeche, in the Yucatan Peninsula, Pomuch is a small town of just over 8,000 inhabitants away from the tourist routes, where every year, the dead are worshiped in a unique and characteristic way.

A few days before November 2nd, the houses are prepared for this celebration by mounting the well-known altars, painting walls, doors, and windows, cleaning the trousseau, and cooking the favorite dishes of the deceased relatives. Other traditional dishes are cooked as well, such as "Pibipollo", a large piece of corn dough, stuffed with chicken and cochinita pibil, seasoned with achiote and cooked in ovens buried in the ground.

Before or after this domestic ceremony, Pomuchean families go to the cemetery, characterized by the bright colors of its walls and tombs. There, from the third year after the death of the deceased, relatives dig up the remains of their "muertitos" and lay them out to dry in the sun.

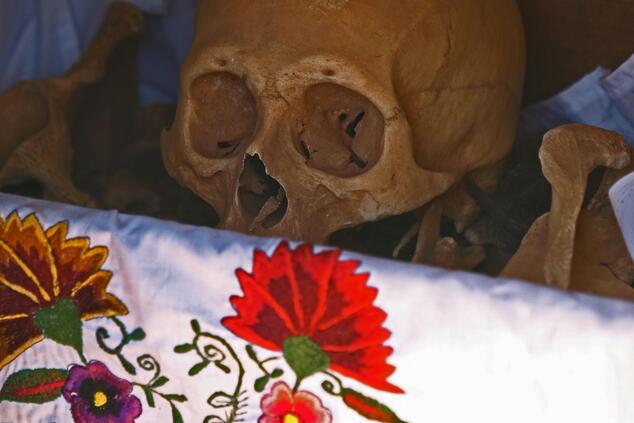

Afterward, they clean them with love and affection, bone by bone, and place them in wooden boxes covered with a white tablecloth previously embroidered with multicolored flowers. Once the bones are in the box, the skull is placed on top, and the lid is not completely closed so that, according to them, the "muertitos" can take in the sun and leave the box whenever they want.

- Every year, families go to the cemetery and remove the wooden boxes containing the remains of their relatives. —

- Their way of honoring their loved ones is to clean the boxes and bones with love and tenderness. —

- Bones are carefully wrapped in fine white cotton tablecloths hand-embroidered with floral motifs. —

- The boxes are kept half-open with the skull visible so that the deceased can continue to see the reality around him. Photos: Jesús Serrano.

This tradition, unique in the country, makes the Pomuch cemetery not a dark and macabre place, but one of light and color, where life and death intertwine, and where in every corner you can feel the love, respect, and care for those who, according to the Mayans, long ago did not die but undertook their great journey to the underworld.