Josephine Peary, the First Lady of the Arctic

Can you imagine a refined and cultured American lady "strolling" among the ice of Greenland at the end of the 19th century? This is the story of Josephine Peary, the first woman who was part of an expedition to the Arctic in 1891, lived with the Inuit, gave birth on the ice, and discovered that Greenland was an island.

At the end of the 19th century, the Arctic was still unexplored territory. On June 6, 1891, a ship named "Kite" set sail from Brooklyn Harbor for that distant and mysterious part of the planet. On board was Robert Peary, the expedition leader, accompanied by his wife, Josephine, who was to become the first female Arctic explorer.

Josephine Diebitsch Peary was the daughter of a Prussian military officer. She was a good student and a cultured and refined woman who, at the age of 19, married Robert Peary, a young naval officer. From the beginning of their relationship, she threw herself into her husband's mission of reaching the North Pole.

During that first expedition in 1891, Robert broke his leg and had to spend several months in bed on the ship. When he encountered a huge wall of ice, he wanted to return, but it was Josephine who convinced him to continue the voyage. So it was while caring for her husband that she took care of all the ship's logistics during the expedition, enduring very harsh and adverse weather conditions.

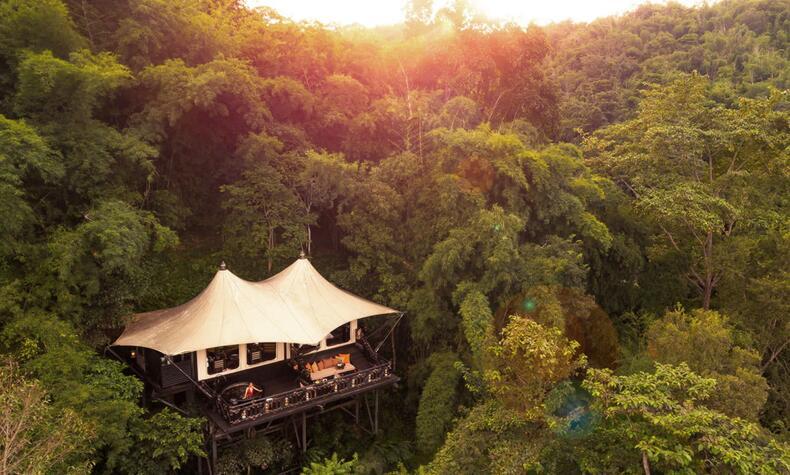

They reached the north coast of Greenland and built a log cabin where Josephine lived for a year among the ice, with her husband and four other men of the expedition. Despite taking care of the household chores, Josephine took advantage of the midnight sun to explore the Arctic landscape and discover the impressive and inhospitable nature of the area, which she would describe in detail in her first book "My Arctic Diary. A Year Among Ice and Eskimos", which she would publish in 1893.

Josephine also established a relationship with the local Inuit Eskimo community, especially with the women, through whom she discovered their dramatic living conditions and their harsh customs in a very macho environment.

In her diary, she tells how the lives of these women inside the igloos were, the violent abuse they suffered from their husbands, some cruel customs such as infanticide among widows, and even the first documented case of a psychic disorder that the Inuit call Pibloktoq, related to the lack of sunlight, cold, and social isolation that mainly affects Inuit women.

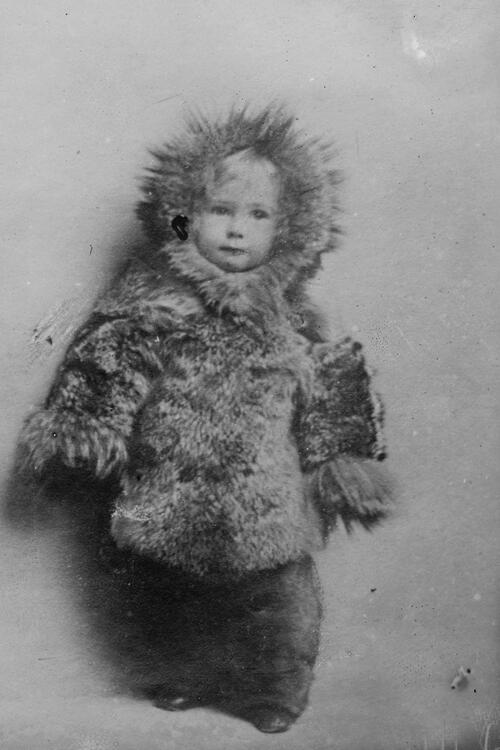

In 1893, eight months pregnant, she returned to accompany Robert on his second expedition to the Arctic, where she gave birth to their daughter Marie, who was baptized by the press as "The Snow Baby", the name of Josephine's second book in which she recounted her experience of motherhood in such inhospitable land.

Marie's middle name, Ahnighito, is the Inuit word for meteorites that had fallen on Greenland thousands of years ago. In 1894 Robert Peary enlisted the help of a local Eskimo guide, who took him north to Cape York, where he located the large iron masses.

Peary took three years to organize and carry out the loading of the heavy iron meteorites onto the ships and sold the pieces for $40,000 to the New York Museum of Natural History, where they are still preserved.

Over the next few years, Robert Peary was repeatedly absent from home in his quest to reach the North Pole. In 1900, during a new expedition, the explorer suffered the amputation of eight toes due to frostbite. Josephine did not think twice and set out to help her husband.

The ship on which she was traveling suffered an accident with an iceberg and forced Josephine to spend the winter in Greenland, 300 kilometers from the camp where her husband was. There, she discovered Robert's infidelity with Allaka, an Inuit woman with whom Josephine continued to live, despite knowing that she was expecting the explorer's child.

Robert Peary achieved his dream of reaching the North Pole in 1909. After achieving that feat, he returned home with Josephine. They remained together until the explorer died in 1920. Josephine outlived him by 35 years. The refined lady of American high society managed to be much more than "the wife of..." and, today, she is considered a pioneer of Arctic exploration, a brave and dedicated woman, as well as a successful writer whose novels are a reference for historians, anthropologists, and scholars of the Arctic and the Inuit people.