Africa is hard to put into words, but I will do my best

Trips to Africa are always full of surprises, whether it’s a return to the origins of life, a glimpse of the delicate balance between species, or an encounter with some of the world’s wildest and most breathtaking landscapes. My journey to Botswana was all of that and more. It began with a long-haul flight to Johannesburg, marking the start of a five-day inspection trip.

After clearing the usual immigration formalities, I had just enough time to pick up a proper safari hat at the airport. Traveling in December, I arrived at the start of Botswana’s summer, the rainy season just beginning to cast its spell over the land. A short layover later, I boarded a final 90-minute flight to Maun, the main gateway to the legendary Okavango Delta. From this small airport, light aircraft depart regularly, bound for the scattered airstrips deep within the delta.

When we picture a safari, our minds often go straight to the dusty savannahs of East Africa, acacia trees silhouetted against open skies, as seen in parts of Kenya or Tanzania. But the Okavango Delta tells a very different story. Here, arid landscapes vanish. In their place, a mosaic of lush green grasses and winding freshwater channels stretches across the horizon, creating one of the richest ecosystems on Earth, an endless sanctuary teeming with life.

Sustainable Safaris

My first stop: two nights at Zarafa Camp, one of the signature properties within the Great Plains Conservation portfolio. Tucked into the eastern edge of the 130,000-hectare Selinda Private Reserve in northern Botswana, Zarafa sets the tone for a journey rooted in purpose.

Great Plains Conservation stands as one of Africa’s most compelling examples of how tourism can be harnessed to uplift the continent, its people, its wildlife, and its landscapes. The organization’s mission is bold: to safeguard vast swaths of African wilderness, including its communities and endangered species such as the black rhino, by blending low-impact luxury with high-impact conservation. Across more than 400,000 hectares, its network of exceptional safari camps serves not just as accommodations, but as engines of environmental stewardship, using ecotourism to fund and fuel vital preservation efforts.

So, who are the visionaries behind this ambitious initiative? The group was founded by five entrepreneurs, including Mark Read, former president of WWF South Africa, and Dereck and Beverly Joubert, the world-renowned filmmaking duo and tireless conservationists. Together, they merged their deep knowledge of photographic safaris with a shared dream: to create what they believe to be the most innovative and environmentally conscious safari camps in Africa.

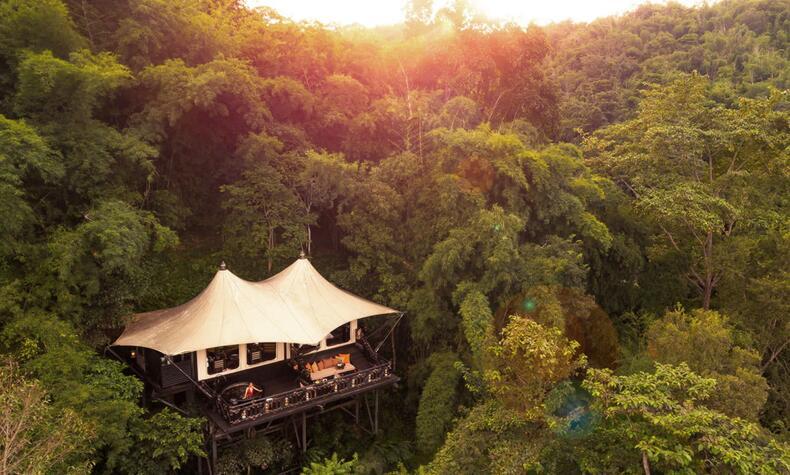

After several trips to Africa, I was still taken aback upon arriving at Zarafa Camp. It was here that I truly understood what an authentic safari experience could be. This intimate four-tent lodge, accommodating no more than eight guests, is seamlessly woven into the natural surroundings, evoking the romance and adventure of safaris from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Think Henry M. Stanley’s Africa: leather campaign chairs, antique wooden furnishings, copper-accented bathrooms, and open-air showers, all brought together in a refined blend of vintage elegance and sustainable design.

That first night was unforgettable. Dining under the stars, we were served a beautifully crafted multi-course meal in an atmosphere unlike any other—surrounded by the sounds of hippos and buffalo in the distance. Each dish was more impressive than the last, a testament to the camp’s commitment to culinary excellence even in the most remote of settings.

Zarafa Camp’s commitment to conservation is evident in the smallest details. Plastic is nowhere to be found. Instead, every guest is provided with a reusable aluminum water bottle, which can be refilled throughout the day at the camp’s bar with fresh, filtered water.

Over the course of two nights, I experienced Africa's most raw and intimate self. Within the private Selinda Reserve, there were no crowds, just vast wilderness and wildlife in abundance. Massive elephant herds wandered the dry delta in search of water ahead of the rains. Elusive leopards moved silently through the trees, stalking impalas with effortless grace. And everywhere I looked, newborns like warthogs, kudus, giraffes, signaled the vibrant pulse of life in this untouched corner of the continent.

The lion's roar can be heard up to 9 kilometers away. It helps them to find other lions and also as a way of marking their territory. Males control large territories and out of jealously, guard their harem of lionesses.

After a full day out on safari, I never could have imagined what awaited us that evening. As the sun began to dip over the horizon, we arrived at the edge of a small lake where a herd of elephants was cooling off in the fading light. There, the team had set up a surprise: a small sundowner gathering complete with cocktails and light bites, all just meters away from these majestic creatures.

Stepping down from the vehicle, surrounded by the stillness of the Okavango bush, I was struck by a sense of awe. In the hush of twilight, I tried to grasp how these nearby giants were communicating with one another, through subtle movements, low rumbles, and quiet grace.

A few canoes were waiting by the water’s edge, and I didn’t hesitate. I climbed into one with one of the rangers and paddled out for a closer look. Drifting gently across the lake, eye to eye with the elephants in their natural element, I felt a profound sense of connection, an experience both humbling and unforgettable.

My next stop on the Great Plains Conservation circuit was Selinda Camp, located in the northern part of the reserve that shares its name. We boarded a light aircraft for a quick 30-minute flight, followed by a 40-minute drive across the bush. Interestingly, during the dry season, when the delta paradoxically overflows with water, the camp can also be reached by navigating the waterways in a traditional mokoro, a dugout canoe used by locals for centuries.

The Selinda Channel is an ancient and unique waterway that flows in both directions, winding its way through the Okavango Delta toward the Linyanti wetlands to the west, the Savute and Chobe Channels beyond, and eventually joining the mighty Zambezi River near the borders of Namibia and Angola.

Staying along the banks of the channel offered an entirely new perspective on the delta and revealed a side of the wilderness that often goes unnoticed. As we drifted quietly by boat, a flash of color caught my eye. Perched in the papyrus reeds was a malachite kingfisher, resplendent in vivid shades of electric blue and green, with a fiery red beak, orange breast, and bright white neck. Just a few meters away, a giant egret took flight in a graceful arc.

More than 1,000 different bird species have their home here, making it a perfect destination for the most demanding ornithological enthusiasts.

My final stop in Botswana was Duba Plains, the third exclusive camp on this journey and a property recently reimagined in line with the same conservation-forward philosophy as Zarafa. With just five canvas tents accommodating a maximum of ten guests, the experience is one of pure privacy and personalized service. Each tent is exquisitely appointed with premium materials, local artwork, and personal photographs from the camp’s owners. Every tent also boasts a private plunge pool, with hippos often lounging just beyond the edge.

- Access to the camps is always by light aircraft, which allows you to admire the immensity of the Okavango Delta. —

- The camp's tents are fully equipped with all the necessary details. —

- Everything ready to recharge our batteries and continue our safari. —

- During a safari a stop is usually made to enjoy a snack in the middle of the savannah.

Situated in the heart of the delta, Duba Plains offered a different kind of safari. I didn’t encounter large herds of elephants here, but the experience was no less extraordinary. Just days earlier, wild dogs had been spotted in the area, yet despite our best efforts, they remained elusive. After a full day of tracking, we returned to camp completely exhausted, but elated nonetheless. True to form, the Duba Plains team had prepared another surprise: a bush breakfast under the shade of a majestic fig tree. Fresh bread baked over makeshift embers, steaming coffee, and the quiet presence of skittish antelopes watching us from a distance made for a moment of pure magic.

Then came the final day, and with it, my last chance to see the wild dogs. We began the morning with a low-altitude helicopter flight over the delta. It was nothing short of spectacular. From above, the labyrinth of water channels and islands took on surreal shapes, the mosaic of vegetation painting a dreamlike landscape. Herds of zebras and antelopes moved below, birds scattered in elegant flocks, and a lone elephant carved its path through the trees.

After lunch and a quick rest, we set out on what would be my final safari in Botswana. The guide turned to us with a smile, clearly pleased. “We’ve found the wild dogs,” he said. “Let’s go.”

After barely 40 minutes of searching, it happened. Just over ten meters ahead, a wild dog crossed in front of our vehicle, then another, and another. In total, a pack of six lean, restless wild dogs moved with purpose toward one of the last waterholes still standing before the rains arrived, a place where antelopes gather to quench their thirst. The sun dipped low, casting an amber glow across the delta as tension filled the air.

The energy was electric. This was a rare sight, wild dogs so close to the water, a risky move that left them exposed. But they were hungry, and the hunt was on. Their pace quickened, and we followed closely, determined not to lose them.

Suddenly, the pack broke into a sprint. They had locked eyes on their prey in the distance. Our guide turned the vehicle, veering off-road to follow them across the open plains. It became a race—predators on one side, our vehicle parallel to them on the other. The guide explained that during the high-water season, from June to August, this kind of chase would be impossible. The delta floods make land travel nearly impossible; in those months, mokoros are the only way through.

But now, in the dry season, we moved fast. Just meters from the moment of truth, the vehicle slowed to a respectful halt, allowing nature to take its course.

I had just witnessed a wild dog hunt, raw, real, and utterly unforgettable. Without a doubt, one of the most intense experiences of my life.